Hi everyone,

At this point, even far right US lawmakers like the pinched faux-leather football of hate from Georgia recognize the reality in Gaza. It’s easy to lose hope, but we encourage you to support, if you can. You can try the Sameer Project, or any other mutual aid of your choice. If you donate $100 or more today, send us your receipt and we’ll mail you a free record, whatever you like.

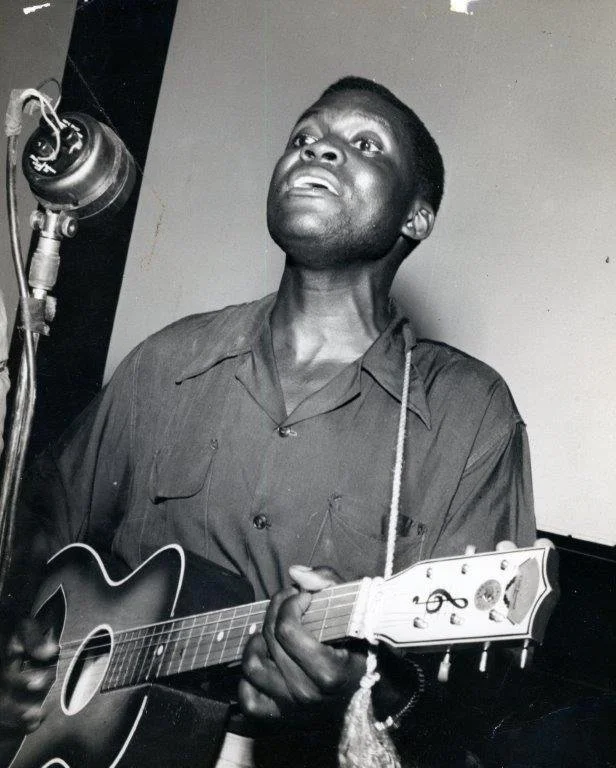

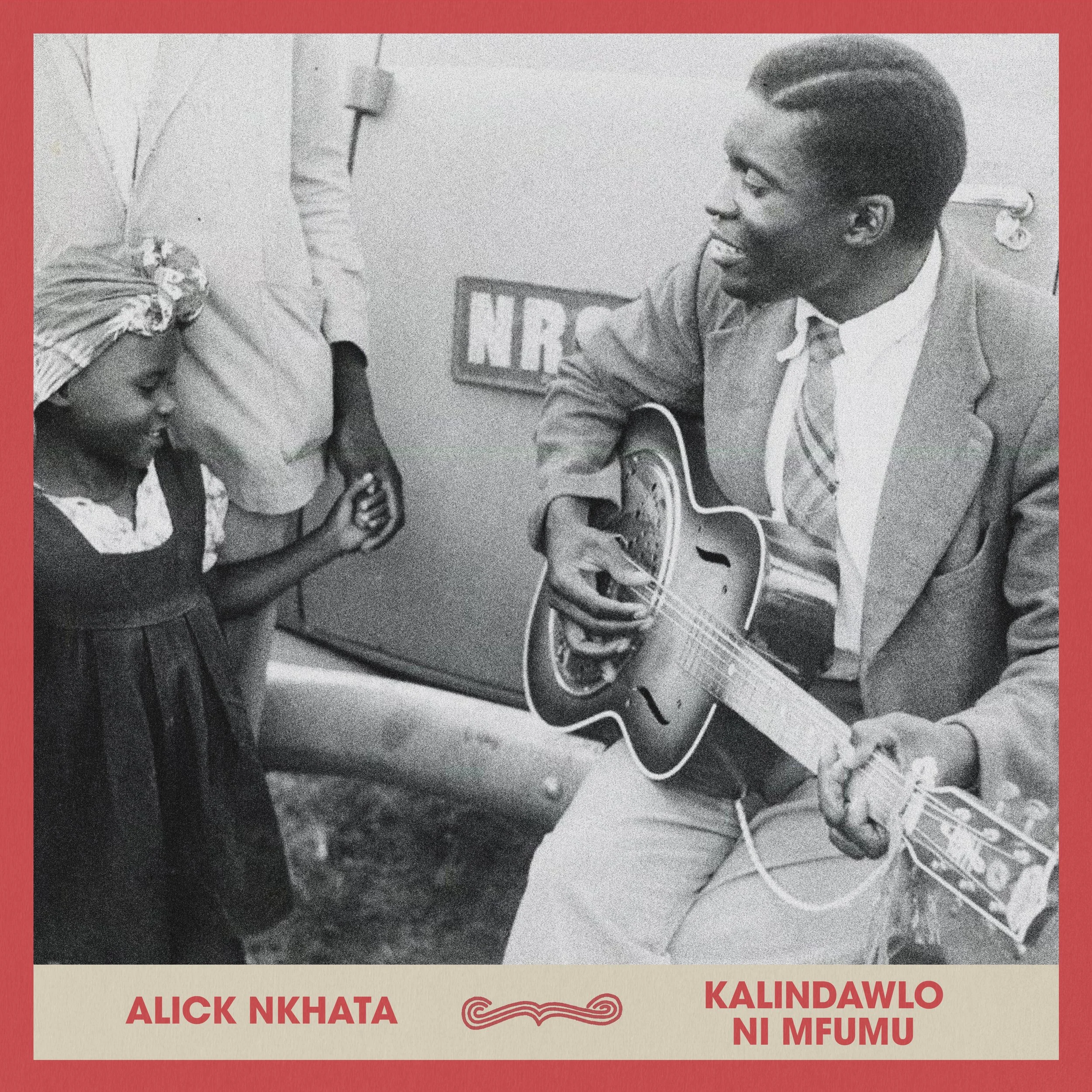

This month, we explore a major new project. Alick Nkhata’s “Radio Lusaka” features the country-western slide guitars, Bemba rhythms, and airtight harmonies of Central Africa’s first pop star. You can listen and order here. Today is Bandcamp Friday, so this is the time!

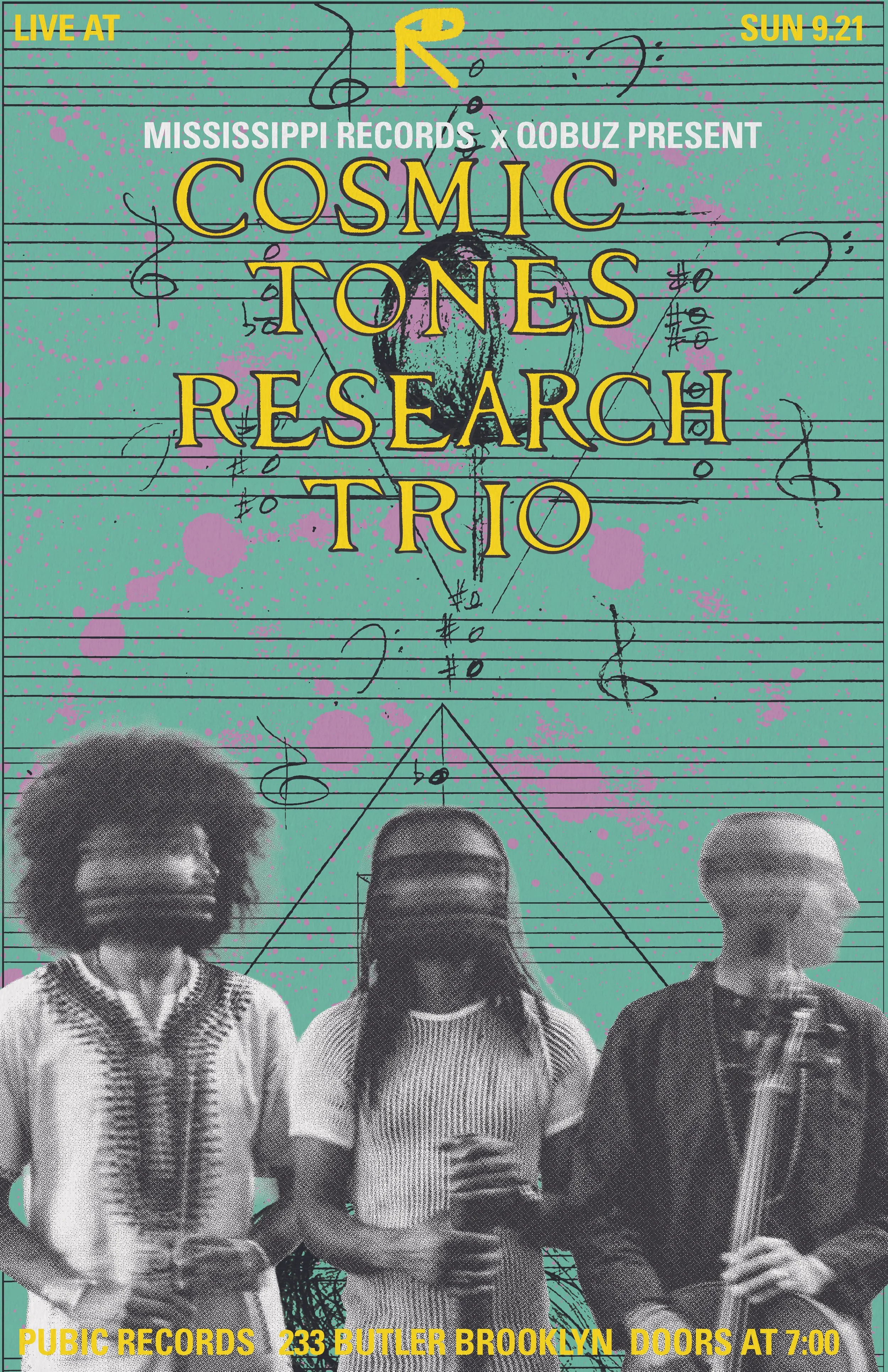

We also share the first single, “Sankofa,” from Portland’s own Cosmic Tones Research Trio, which creates genre-defying and truly healing spiritual music. Please join us for their first ever New York show on Sept 21 at Public Records…

Something connects 75 year old pop hits with up and coming creative musicians. We trace these lineages in an interview with journalist Jamal Khadar, who went so deep on the liner notes to the Alick Nkhata record that he was contemplating FOIA requests from his Amsterdam base.

I also had the privilege to speak with Austin-based author Fernando A. Flores about the connection between music and the exuberant writing in his stunning new novel, Brother Brontë. Fernando is one of many brilliant artists in our Community Supported Records club and we’re planning to highlight more in upcoming newsletters.

We keep making things we want to see, and collaborating with people all over the world to do so. Thanks to you for listening and making this all possible.

Solvitur ambulando,

Cyrus + Mississippi Records

MRI-216

Alick Nkhata

Radio Lusaka

Listen / Order

Country, township jazz, and pop hits from the height of Zambia’s freedom movement. Vocalist, guitarist, and bandleader Alick Nkhata moved effortlessly between lonesome country slide, big band pop, and air-tight vocal harmonies, all with roots in Bemba and other African traditional songs and rhythms. It’s a dizzying, inclusive, expansive blend from an artist and music archivist who became the voice of his nation’s fight for freedom.

MOR-11

Cosmic Tones Research Trio

“Cosmic Tones Research Trio”

Listen / Order

On their self-titled second album, The Cosmic Tones Research Trio—featuring Roman Norfleet, Harlan Silverman, and Kennedy Verrett—dives deeper into the spiritual soundscapes that first defined their genre-defying approach. Based in Portland, Oregon, the trio crafts a transcendent listening experience rooted in both meditative stillness and rhythmic propulsion.

Jamal Khadar is an Amsterdam-based journalist and host of the always excellent Reimagining Country show on NTS Radio. He helped produce our Alick Nkhata album, connecting us with Nkhata’s family and undertaking a prodigious amount of research for the liner notes. I caught up with him about African country music lineages, and the first Mississippi release to lead to a FOIA request…

Huge thanks to Gordon Ashworth for first sharing Nkhata’s music and putting so much time and energy into sourcing material, to Nkhata’s daugther Daisy Nkhata-Ng’ambi and nephew Africa Munyama their collaboration and trsut, Ellen Banda-Aaku for her poetic lyric translations, Michael Kieffer, Rob Allingham, Simeon Allen, and Mark van Yetter for their help with source materials, Jordan McLeod at Osiris Studio for making it all sound so good, Ella Gold for her album artwork, Eli Schmitt for transcribing all these interviews, and of course the fam Sam, Maria, and Adam. This album is dedicated to Nkhata’s son, David Nkhata, who first began research and documentation of his father’s work, but passed before this album could come to be. We hope he’d be proud.

Cyrus Moussavi: What drew you to African country? Or how would you even describe what it is that you're researching and listening to?

Jamal Khadar: I was steeped in country by my parents from a young age, but I think like most people I didn't pay too much attention to it. There's a lot of country, Americana themed stuff in their music collection. I then rediscovered the music as an adult, as people do with their parents' music collections, and just really grew attached to it. It’s beautiful music. There is plenty of stuff wrong with country, but it’s a great way to think about family and lineage and the passing of time.

My dad is from Sierra Leone, my mom is Jamaican, and I was born in the UK. I was interested in the country connection there, because it seems like such a juxtaposition. On the face of it, it seems against everything we know about country. I traced it back, a family project, and it became a way for me to talk to my family about our history. It was how I had the first real conversation with my grandma, and what it was like for her to move to England from Jamaica, and why country was important to her then. It was a great way to think about what was happening for both my grandparents on different sides. Music allows you to see history through people with more nuance than a lot of textbooks.

Country became a way of looking at early 20th century globalization and the way that music traveled around the world and the way cultures collided. Even though it feels like a long time ago, people from all over were traveling and crossing continents and music was going with them. They were starting bands and projects with people from different parts of the world or from different cultures. That's what interests me in all of this. It's the way that country and ideas of America and Americana traveled the world and were kind of twisted and appropriated and found new lives

CM: It's so cool that it brings together the two sides of your family, who were on different continents but were both listening to this music.

JK: Yeah, exactly. Similar artists as well. People like Jim Reeves had such a significant influence on both of my grandparents. It's interesting to see how the same artists, even the same songs, sometimes, have different meanings across cultures. My Jamaican grandma, when she moved to the UK, had a horrible time. I remember she said, “My only friends were the swans in the park.” But this music, in her case, was about transcendence and moving beyond. There was a religious aspect, too. While on the other side of the family, I think it was the storytelling aspect they were interested in.

CM: I imagine Jim Reeves would be shocked to hear all this.

JK: That's something my uncle on the Jamaican side was always conflicted about, like this horribly racist man, Jim Reeves, who at the same time was a saint. There's just lots of sides to it, and it's messy and interesting.

CM: That's what I love about your work. You manage to take this music that is easy to gloss over as very simple and plain, and show us how messy and interesting it actually is.

JK: Yeah, people see it as something plain and pure. When we think of cultures coming together and mixing, we assume it's gonna be complex and explosive and all these things, but no, it's like creole that creolized language. Two people coming together and finding the simplest meeting point. It's complex but also really simple-sounding music that has all these layers to it.

CM: That's a really good description of Alick Nkhata's music. At first it’s a nice pop song. And then you're like, Whoa, this is incredibly tightly constructed. And there are influences coming from multiple continents and time periods at once. How did you first hear Nkhata? And what drew you to him specifically?

JK: Well, I knew Africa Munyama, his nephew. I always had the sense that Africa's family was involved in significant ways in [Zambia’s] history. When I started the radio show, Africa reached out and was like, "Oh, you should check out my uncle's music.” We go back 10 plus years, but had never talked about Nkhata at all.

[Nkhata’s music] had yodelling and very strong early country and western hillbilly guitar influences. But he’s also in a suit, and it was hard to tell what was going on. Digging into the history, I realized the guy lived such a life. He was coming up everywhere I looked - he worked with Hugh Tracy, he was there during World War II when there was this exchange of influences and sounds, he was there at the beginning of African radio, full stop, on the continent. He was an independence figure who was there in Zimbabwe during the struggles.. There is also this tension with him being involved with the British colonial influence while also being an activist figure, which complicates the easier and more common story we have around that time.

CM: When I heard you on the radio, I was like, this is my guy. At first, I just heard you play an Alick song. But then I heard you talking about the history, and then interviewing his family. You kept going! I was like, oh, this guy is deep. You ended up doing a huge amount of research for the liner notes of the record. Can you tell me about your process?

JK: I was spending a lot of time in the archives and occasionally sending you photos. What I tried to do was firstly talk to experts who had studied his work. We have to shout out Ellen Banda, who is a family member [of Nkhata’s] and who has a documentary on Nkhata. She was already in the process of doing so much research for years. Speaking to people like Dr. Robert Einstein who’d done loads of research into Alick Nkhata’s radio career working at various African studies centers in Germany and Paris. I then tried to go one layer deeper and be like, who actually met him and was in the room with him. It started incredibly broad, but I felt like there was an end in sight by the time you made me turn in the liner notes. But I still was like, we need to do a FOIA request. Because there’s a possibility that he was involved with the American government in some way. Given his influence in Central African Independence politics, and given that he went to the US and worked for Voice of America as one of the first African hosts, I hope somebody takes this up as a book project and goes further, 'cause there's endless potential here.

CM: What else surprised you in your research?

JK: At first, it was just the messiness of the power relations. The fact that he was both working very closely within power structures and the British colonial establishment, but also over time becoming involved in the independence politics. I didn't know what to think; it was really hard to tell what his beliefs were and how much those changed over time. But it was a good reminder that there are different forms of activism in different contexts. We're used to very visible signs and a very clear story of somebody who's a “musician activist.” But it's more complicated, because, like a lot of people who end up in independence movements, they take advantage of opportunities within the power structure. And for the first people through the wall, there are different ways of protesting.

More recently, the main surprise is the contemporary mining story. The fact that all of this started one hundred years ago in Zambia with the British South African Trading Company discovering vast copper mines and bringing people to the region, turning it into a melting pot, that's how the music started. That led to Zamrock later. And Zamrock's spectacular collapse midway through the 80s was also the collapse of the copper industry.

But there is a modern story I found in the later stages of doing the liner notes, where China and the US are now starting the cycle over again. You can’t make this stuff up. Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos using AI to map the terrain and discover these incredibly vast, rich copper deposits, as well as cobalt, and other minerals which we need for smartphones and AI. It's just the same cycle, really. And the fact that that's happening at this Trump, new imperialist moment is very crazy to me. It seems a really poignant moment for Alick’s record to come out.

CM: I’ve been thinking of Alick as a political person, and how we can’t quite pin him down. And art and its connection to politics in general. Could you talk a bit about the role Nkhata’s music had in Zambian independence?

JK: I think his story really tells us what resistance looks like pre-independence. It starts after WWII, when people are coming back with new influences and attitudes. I couldn’t always tell you where he stood, but through his work, I was left with the impression that he had a fairly consistent view of the importance of Zambian culture and traditions, and how modernity should work for Zambia. He has that full journey from the political awakening to the subtle resistance, through to independence politics, and through to becoming a member of the establishment himself.

That's the beauty of the music, the tension and toeing the line. He couldn't be explicitly political at all times, but there's a lot of social commentary in the lyrics. And the product of all of his radio work and all of his music work was building a national identity. We also have to remember, he was really the first African voice on the radio for many Central Africans and the first kind of pop star for many Central Africans.

Looking back at his story and his music, it's almost a eulogy for a certain type of American cultural power and influence. Particularly right now, when America seems to be withdrawing from the rest of the world. It’s a look at how American influence traveled through globalization. How that influence is up for grabs and is twisted and used to explore local identity.

CM: What is the connection to Zamrock? Can you say that Alick was a precursor, or is it just a coincidence?

JK: I think it's great that Zamrock is so well known for its incredible story and music, but that intense focus has a way of flattening the diversity of Zambian music and its history. So maybe we can't necessarily say that Alick Nkhata led to Zamrock, but that rich history of mixing influences and creating new sounds in the copper belt started with Alick in lots of ways. All of that stuff is what people appreciate about Zamrock - that it was mixing sounds and that it was political in its own way. There's a long history of that approach in the region, and it starts with Alick.

Jamal Khadar is a journalist and the host of the always excellent Reimagining Country on NTS radio. His deeply researched liner notes accompany MRI-209 Alick Nkhata - Radio Lusaka, which is up for pre-order now. The record is pressed on high quality black vinyl, mastered at Osiris Studios, and the album also includes lyric translations by noted Zambian author Ellen Banda-Aaku.

“Kalindawalo Ni Mfumu” Out Now

Full album “Radio Lusaka” Out 8/15

The second single from Alick Nkhata’s “Radio Lusaka” is out now! Listen to “Kalindawalo Ni Mfumu” HERE

CSR INTERVIEW WITH FERNANDO A. FLORES

Mississippi’s Community Supported Record club has been part of our whole deal since the earliest days. Back then, there was no website, and Mississippi was only available in a handful of shops. And what about the people who lived in the vast tracts of this country where there wasn’t even a record shop? Well, you could send a crinkled wad of cash and (if all worked as planned), you got our records as they came out. Those brave supporters made it possible for the label to take risks and keep pressing music.

We’ve updated things a little bit, but the spirit (and function) is the same. The CSR members sturdy enough to tolerate the vagaries of the Mississippi pressing schedule are unique people indeed. Many of them are also artists and producers of artifacts. We’ve long wanted to speak with them about their work and how music fits in. Hence this new column.

The other day I finished a remarkable book called Brother Brontë by Fernando A. Flores, a writer, book seller, and longtime CSR member in Austin, Texas. It’s set in a not-too-distant dystopian future where all mothers live and work in a fish cannery and the people on the desolate streets dodge toxic sludge clouds, book burners, and hostile neighbors. A badass pair of young women reminisce on their days in a punk band and fight to stay alive with help from some militant tias and a wounded tiger.

“Rain fell hard like slabs of ham,” the book begins. Fernando twists and refracts language, reminding me that English wasn’t always as anemic and limited as it feels today.

At the end of the book, the very first acknowledgment reads - “Couldn’t have been finished without cosmic help from: Nina Simone’s 1969 Rome concert version of ‘Suzanne.’” Obviously the writer is our kind of people. Further along, though, I’m surprised to see shoutouts to the great Brother Theotis Taylor, Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru, and finally to Mississippi Records itself! Like we’d given some fuel to a book that in turn gave us so much joy…

So I had to call Fernando, and he gave me this answer in pretty much one glorious uninterrupted passage…

Cyrus: Fernando, how does music relate or inspire your writing, and your creative work in general.

Fernando Flores: I wish I had a direct answer because it always seems to change. You know, back in 2007, I got hired to work on a documentary film, in Baja, 18 hours south of Tijuana. I was a sound operator. We're in the middle of nowhere, we were interviewing these fishing communities that, because of climate change, were seeing less and less fish every day. Well, there was this one day when this boat came back full of fish… so many fish, and it was such a good day, everybody was so happy to see this. But I remember one of the fishermen saying, “You know, it's good right now, but the fish remember.” So, just because we found fish here, it doesn't mean that tomorrow we'll find any, cause the fish remember. And that's how I feel about creativity. Just because you find something once doesn't mean you can keep finding it. So you always gotta be open to new avenues.

I'm always thinking about the 20th century. It has a lot of lessons that are there for the taking. Because of the way mainstream media works, lots of small artists are left behind. So I'm slightly obsessed with discovering art scenes, and movements, and music from all over. I'm always impressed with how much I don't know. I remember watching Susan Sontag on Charlie Rose. He asks a question and she says “You’d be shocked at all the things I don’t know.” And that's how I feel about music, about everything.

You know, sometimes as a writer, I feel like I'm the least important person in the writing process. My job is almost like a medium. Sometimes characters just appear in my work, and I'm like “Who is this person? I don't know you.”

There is a character in Brother Brontë, her name is Bettina. She's a peripheral character. In my book, there is a fish cannery where most of the mothers are pretty much forced to work by the government, and she works there. She's an older character, and for a long time, I asked “Who is Bettina?” And I had a really hard time connecting to the character, until I got that Brother Theotis Taylor record in the mail. And especially that second track, I Have a Friend. I would just play the record over and over again. There's something there, you know, listening to them talk and laughing in the background. And I finally found some kind of connection to the character and the mechanics of the fish cannery, how it was going to work, as I was playing that record over and over. There is an energy it gives off. I believe that there is an energy you’re able to give off when you're writing to a receptive reader. You establish a connection, and that was what that record did for me. I can't tell you what it is, but it's magic.The spirit is in the piano, the way it was recorded. Nothing sounds like that. I think I could hear that piano and know exactly who is playing. I'm sure it's the same for you.

That's the stuff that you can't find just anywhere. It's not gonna just come to you. So I really search for music and other people’s art, just try to connect, you know?

I really think that you, Mississippi Records, provide that service to the collective unconscious, putting lost things into the world that is dominated by technology and streaming. And I try to be present in the moment, because I feel it's my duty to connect with what artists are doing.

People tend to separate mediums of art. The filmmakers are over here, the visual artists are over here, the writers are over here, the musicians are over here. And to me, I don't know, I hate to glamorize the past, but to me, it feels like there was a time where it wasn't so insular, where everybody was in communication with each other. And that's what I strive for. I strive to break down these illusions of the difference between mediums. It's all part of the same conversation in the end.

Fernando A. Flores' latest novel, Brother Brontë, can be picked up (signed!) from Alienated Majesty books in Austin, TX, or fine independent bookshops anywhere.

Spots are open in our new, improved CSR. Save about 20% on all our releases and support the label directly. Sign Up Here!

During a terrible two weeks, while friends and family ducked for cover in Iran, we went back to the archives of Iranian songs for comfort, and put together this playlist of devastating songs from over 100 years of recorded Iranian music:::

Meanwhile, on a recent tour of Japan, Mississippi’s own Sam Wenc picked out these bangers:::

NYC:

Mississippi Records x Qobuz present:

Cosmic Tones Research Trio

Please welcome Portland's Cosmic Tones Research Trio to Public Records for their NYC debut. This promises to be a very special show. Copies of their new self titled LP will be available.

Sun, Sep 21

7:00 PM Doors

Public Records

233 Butler St, Brooklyn, NY

TICKETS HERE

PHILADELPHIA:

Making Time Festival

Mississippi Records DJs spin for their lives at one of the nation's greatest and weirdest festivals.

Fort Mifflin

Philadelphia PA

Sept 19-21st

TICKETS HERE

And for our friends on the Australian content, don't miss Mississippi founder Eric I's tour of outback!

Eric Isaacson will be on tour presenting his “History of North American Music” talk in Australia! For our friends out that way, be sure to attend if nearby

GYMPIE - Art Post - Thursday August 14th

LISMORE - Star Court Theatre - Saturday, August 16th

BRISBANE - Cave Inn - Friday, August 22nd

MELBOURNE - Cinema Nova - Tuesday, August 26th

SYDNEY - The Golden Age - Wednesday, August 27th

COMMUNITY LINKS:

EMAHOY TSEGE MARIAM MUSIC FOUNDATION

The non-profit organization Emahoy established in order to channel her royalties into music programming for kids in Ethiopia and the US.

Mississippi Records Portland Store

Visit our friends at the Mississippi shop!

They are open EVERY DAY from 12 to 7 PM!

(The stereo repair and retail shop is open Friday - Sunday, 1 to 6 PM).

WE ARE EXCITED TO BUY YOUR RECORD COLLECTIONS!

Mississippi Records Bandcamp

There are hours and hours worth of albums available for free listening, and a whole lot of the releases are "pay what you want" if you want to download ‘em.

Red Hook Mutual Aid

We’re proud to have a studio in Brooklyn’s Red Hook neighborhood, which hosts one of the most active mutual aid groups in the city.